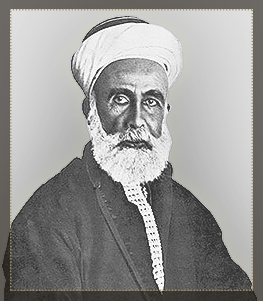

Sultan Abdul Hamid II ruled the Ottoman Empire during the last quarter of the 19th century. His reign witnessed one of the most dangerous phases involving the Eastern issue, and the state faced a disaster more violent than all it had faced before. The Ottoman state then came to be known in Europe as “the sick man”.

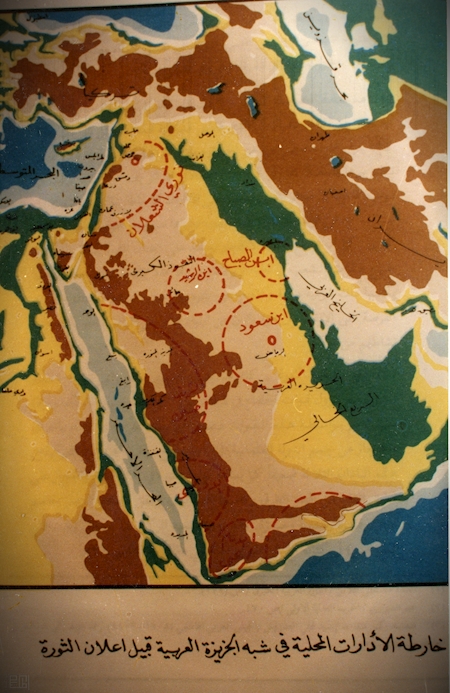

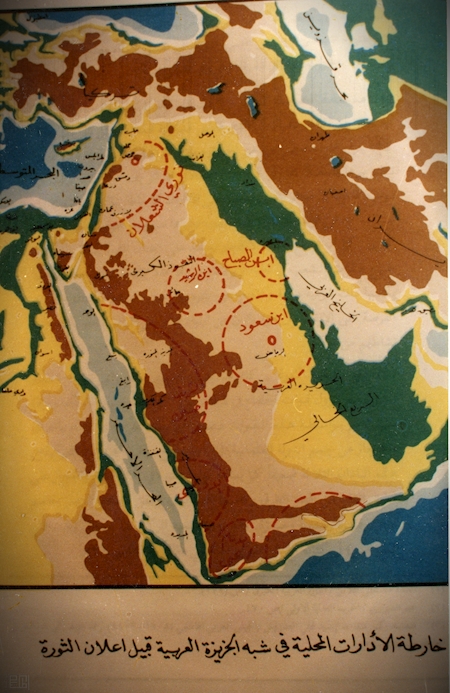

The Sultan was aware of the prevailing sense of resentment and the rise of revolutionary movements in the state’s Asian parts, which caused him to panic, especially since Arab states had a greatly decentralised administration. As a result, he increased Istanbul’s control and gradually began to impose an iron fist rule on them.

In the early period of his reign, Abdul Hamid had to accept Midhat Pasha’s constitution, becoming a constitutional monarch for some time. On 19 March 1877, the Ottoman parliament met at the large reception hall of the Dolmabahçe Palace, where it listened to the Sultan’s speech from the throne. But the Sultan issued an order to dissolve parliament and suspend the constitution indefinitely. He also had the enlightened members of parliament, who had been known for criticising Ottoman rule and mismanagement, leave Istanbul. Those lawmakers included a number of leading Arabs.

The policy of repression of freedoms practised by Abdul Hamid pushed reform and political opposition movements to work in secret or beyond the borders of the Ottoman Empire, especially in Paris, London, Geneva and Cairo after the British occupation of Egypt in 1882. This marked the rise of secret societies that worked to introduce reform in Arab countries, or — in a more radical approach — sought to liberate Arabs from Turkish rule and any foreign control.

Revolutionary Pamphlets

Once anti-Turk movements grew stronger, they started distributing revolution pamphlets around the cities of the Ottoman Empire. On 9 October 1879, the consul in Beirut, Delaporte, who had apparently been aware of the presence of a secret society in the city, filed a report to Waddington, the foreign minister, reporting a possible Arab plan involving communications in Aleppo, Mosul, Baghdad, Mecca, and Medina to establish an Arab Kingdom.

The consul added in his report that the issue came from rumours, and that he was not in a position to confirm them. But he maintained that the total chaos and mismanagement plaguing the Ottoman Empire meant that it is neither impossible nor improbable to accomplish such a plan.

For his part, the French consul in Beirut, Sonquis, mentioned, in a letter sent to the foreign minister on 2 June 1880, the recent appearance of pamphlets in Beirut and Damascus calling for the independence of Syria. The leaflets were small and hung after midnight on the walls of streets close to the consuls of major countries around Syria’s cities, especially in Beirut, Damascus, Tripoli and Sidon. They addressed Arabs, in an attempt to appeal to their patriotism and glorious heritage, urging them to rise and revolt to drive Turks out of Arab land.

On 28 June 1880, the British acting consul-general in Beirut sent a telegraph to the ambassador in Istanbul informing him that the placards had appeared in Beirut, “calling upon the people to revolt against the Turks”.

Other pamphlets also surfaced. In Baghdad, a revolutionary pamphlet in Arabic, clearly printed in London, appeared, urging the Arabs and Christians of Syria to unite and free the Arab nation from the Turks. The leaflet, dated 19 March 1881, was titled “A Call to the Arab Nation” by the Society to Protect the Components of the Arab Nation. However, these pamphlets should not be over construed as part of an organised, wide-reaching attempt by Arab Muslims to secede from the Ottoman Empire and establish an independent Arab state.

Enlightened Muslim leaders were not thinking of violating Ottoman sovereignty, which was an Islamic one, nor of seceding from the Ottoman Empire, which was the only remaining strong Islamic empire. They sought self-rule or internal autonomy within the Ottoman Empire.

Deterioration of Internal Affairs

By the end of the 19th century, the internal affairs of the state continued to deteriorate further, with discontent, corruption and chaos alarmingly spreading. In early February 1894, the French ambassador in Istanbul sent a report on the Armenian issue to Foreign Minister Casimir-Perier, saying that such conditions were not limited to Armenia, but includes the entire empire. He cited Greece, Albania and Arabs as examples of those sensing a lack of justice, government corruption and no security.

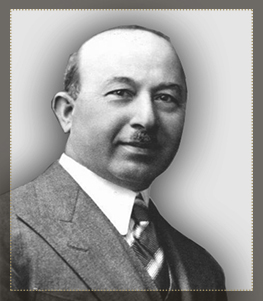

Members of the “Young Turks” movement were working at the onset of the 20th century to rescue the Ottoman Empire from complete dissolution and demise. The society sought to establish a parliamentary government by reinstating Midhat Pasha’s constitution of 1876 and putting a stop to the meddling of European countries into its affairs. The movement led its operations from Thessaloniki in Macedonia, where it successful gained the favour of the stationed military units.

The July 1908 revolution forces Abdul Hamid to reinstate the 1876 constitution — a move met with Arab and Turkish jubilation, as well as parties, receptions and festivals. The words “liberty, equality and justice” were etched into the Ottoman flag. However, Abdul Hamid had been determined since day one to dispose of the Young Turks, the constitution and the new parliament. On 13 April 1909, an attempt for a counter revolution was made, but the army in Macedonia, led by Shaukat Pasha, was ready, moving into the capital and surrounding the Sultan’s Yıldız Palace. On 27 April, Abdul Hamid was deposed and banished to Thessaloniki.

It later transpired that the Young Turks movement was not planning to honour its promises to grant equality to all Ottoman subjects without discrimination on the basis of religion or gender, an issue that caused a rift between Arabs and Turks. Arabs grew doubtful of the Young Turks movement, whose radical tendencies were at odds with Arab’s dignity, pride and their dedication to their nationalism, religion and language.

Arab Separatist Movement

One can assume that the seeds of the Arab separatist movement started growing through the nationalist Turkish policies in place from 1909 and thereafter. The policy of “Turkising”, adopted by the leaders of the “Young Turks”, was a major motive for Arab leaders to seek national independence. While members of the Committee of Union and Progress had nationalism as their highest ideal and in their ethnic superiority a basis for a new strong Turkey that is politically and culturally united; Arab leaders were thinking of the future of Arab states in the same manner.

As a result, enlightened Arabs and intellectuals founded a number of societies and political parties to defend the Arab cause and protect the rights of Arabs. These societies, established after 1908 AD, included the following: Arab-Ottoman Brotherhood Society, the Literary Forum, the Qahtani Society, the Green Flag and the Covenant Society, which were all founded in Istanbul. In addition, the movements included the Beirut Reform Society, the Basra Reform Society and the National Science Club, founded in Baghdad. Moreover, there were two important organisations — Al Fatat (The Young Arab Society) and the Ottoman Decentralisation Party.

Arab Demands

Through these societies, especially Al Fatat and the Decentralisation Party, Arab leaders called for a constitutional parliamentary government that guarantees equal rights and opportunities for all the different components that make up the Empire.

The Arabs also called for making Arabic an official language alongside Turkish in the Arab states of the Ottoman Empire. However, the Committee of Union and Progress were more dedicated than ever to keep the Empire Turkish “in form and character” and to maintain their dominating privilege.